The Causeway Way is a long distance path of some 50 km, that starts near Portstewart, at the mouth of the river Bann, and ends at Ballycastle. It passes through Portrush, Dunluce, Bushmills, the Giants Causeway, White Park Bay and the famous Carrick-a-Rede rope bridge.

The North West 200 is a motorcycle race meeting held each May. It is run over public roads between the towns of Portstewart, Coleraine and Portrush (the Triangle) and is one of the fastest in the world, with speeds in excess of 200 mph (320 km/h). In practice for the 2012 event Martin Jessop was clocked at 208 mph (335 km/h). The first meeting was held in 1929. It is the largest annual sporting event in Ireland, attracting over 150,000 visitors for the weekend.

There have been 16 deaths since the event was first held, with three in one day in 1979.

The path of the Causeway Way follows the northern leg of the NW200. My father’s farm was on the road, just south of Carnalridge.

At the edge of the headland at Portrush, between the port and the recreation grounds is a disused quarry, in which is today located a water amusement park. Originally it is believed that this was the site of Portrush castle which, together with the church, was ransacked and destroyed by the army of General Munroe in the late 1600s. It was later demolished to create the walls of the harbour.

It was Richard Óg de Burgh who built the first castle at Dunluce, on the cliffs adjacent to the White Rocks, near Portrush. The castle was first documented in 1513, as being in the hands of the McQillan family. They were Lords of Route from the late 13th century, until they were displaced by the McDonnells in the late 15th century.

In 1588 the Girona, a galleass from the Spanish Armada, was wrecked on nearby rocks in a storm. Of the 1300 men on board, only nine survived, and were eventually transferred to relative safety in Scotland. About 260 bodies were washed ashore. In 1967-8 a team of divers located the wreck and much treasure and other valuable items were recovered and are currently held at the Ulster Museum in Belfast.

Following the Battle of the Boyne and the defeat of James I in 1690, the McDonnells were impoverished, and since that time the castle deteriorated and parts were scavenged to serve as materials for nearby buildings.

In 2011, major archaeological excavations found significant remains of the “lost town of Dunluce”, which was razed to the ground in the Irish uprising of 1641. Lying adjacent to Dunluce Castle, the town was built around 1608 by Randall MacDonnell, the first Earl of Antrim, and pre-dates the official Plantation of Ulster. It may have contained the most revolutionary housing in Europe when it was built in the early 17th century, including indoor toilets which had only started to be introduced around Europe at the time, and a complex street network based on a grid system. 95% of the town is still to be discovered.

Bushmills is a village some 8 km east of Portrush, along the coastal road. The river Bush passes through the village. It is home of the world-famous Bushmills Whiskey. There used to be five distilleries in the region, but only one now survives. The distillery draws its water not from the river Bush, but from one of its tributaries, Saint Columb’s Rill.

King James I granted a licence to distil in the area in 1608 and Bushmills claims to be the oldest licenced in the world. In 2005 the company was acquired by Diageo, but now is in the process of changing ownership with José Cuervo.

Close to Bushmills is the Giant’s Causeway, an area of basalt columns that descend into the sea. The Scottish island of Staffa has similar rock formations. There are approximately 40,000 columns, typically with five to seven sides and measuring up to 25m in height.

When we moved in to the new house at Islandflackey in the early 1950s, my mother bought a load of five-sided causeway stones, to use in her garden as borders. I cannot imagine that today that they are quarried in the same manner.

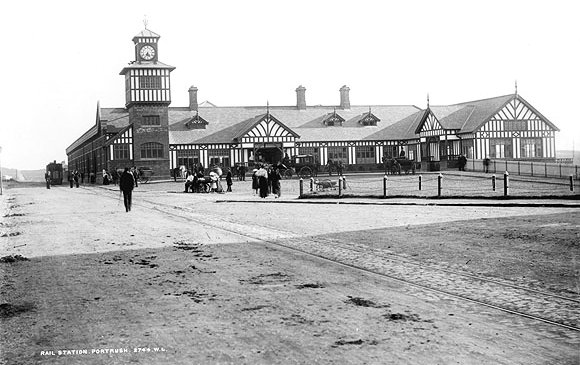

The Portrush to Bushmills tramline was the first in the world to be powered by hydroelectricity, by water turbines installed in a generating plant at Wakemill Falls outside nearby Bushmills. The service started in 1883, with an extension to the Giant’s Causeway in 1887. The line ran from Eglinton Street, beside Portrush railway station and the distance to the Giant’s Causeway was about 15 km.

Initially there was considerable mineral traffic from quarries along the line to shipping in Portrush harbour and there was goods traffic to Bushmills. By 1900 this business deteriorated and the line relied on tourist traffic, supplemented by military operations during WW2.

In late 1949, operations ceased, and the line was dismantled. The section from Bushmills to the Giant’s Causeway was reconstructed and opened at Easter 2002.

From the Giants Causeway, the path follows the cliffs until one arrives at White Park Bay, and a little further on, the Carrick-a-Rede rope bridge.

There has been a rope bridge there for more than 250 years. It was used by fisherman laying their nets to catch salmon that used to pass by there, on their way to their spawning rivers.

The Causeway Path ends at Ballycastle, the port for access to Rathlin Island. Ballycastle is known for its Ould Llamas Fair, held every year on the last Monday and Tuesday of August. The fair has been held for at least 400 years and it probably started as a market at the end of the harvest season These days there are more than 400 stalls and traffic is grid-locked for miles around.

When I was young, I recall being given a packet of dulse from the fair. Dulse is a reddish edible seaweed, very salty, but allegedly quite nutritious.

I have a long-held ambition to walk around Ireland. When I finally set out, the first stage will be on the Causeway Path.